NOISE-Gallery

Media Farzin, Marwan, Yoshua Okon, Babak Radboy, Bassam Ramlawi, Mounira Al Solh

Andree Sfeir, Rayyane Tabet, Lawrence Weiner, Alessandro Balteo Yazbeck

Between the first generation of post-9/11 cultural survey shows and the reflexive gymnastics of the next generation—which aimed to problematize the legitimacy of yet another regional survey while managing, miraculously, inevitably, to deliver one—Bidoun attempts to close its eyes and tune its ears to the white noise of the white cube, wondering how much it matters which city, region, country, or peoples surround it.

As it happens, it does matter, but perhaps not in ways expected. Rather than curating works to illustrate problems plucked from a readymade critical lexicon, NOISE attempts to let these problems arise from, and give rise to, the works themselves, opening the door to the unexpected, and even to the uninvited. The exhibition’s point of departure is the space itself. Its location in Beirut gives it its critical acoustics, but it retains the conceited platonic generality of any clean post-industrial art space, anywhere in the world.

Gallery Walk-

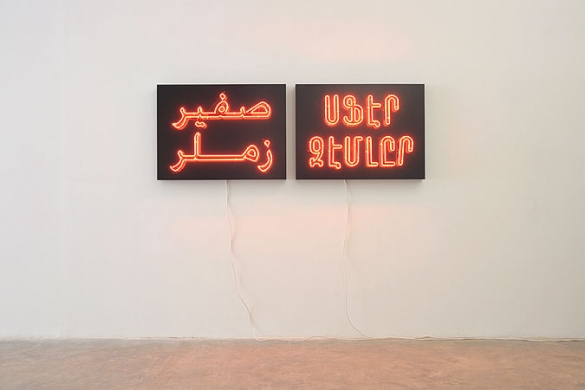

Vartan Avakian has installed a red neon sign on the roof the previously unmarked gallery building spelling SFEIR-SEMLER in the Devangari script. Visible for miles it faces the Armenian neighborhood of Buorj Hammoud, where the newly emigrated south Asian community has taken root. Inside the first room of the gallery hang two more signs by Avakian, one in Armenian and one in Arabic, one turned on and one turned off— both simply spelling out the name of the gallery, subtly demonstrating identification is always divisive, common ground displaced by property and languages neither neutral nor equivalent.

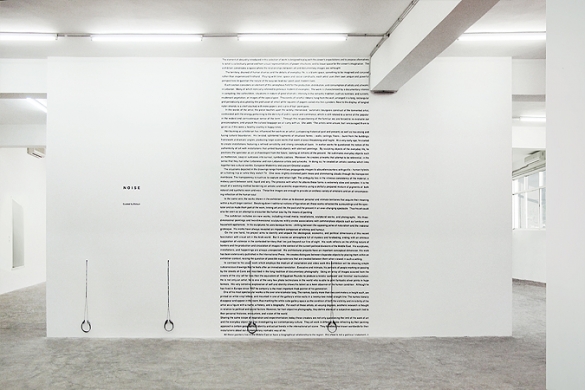

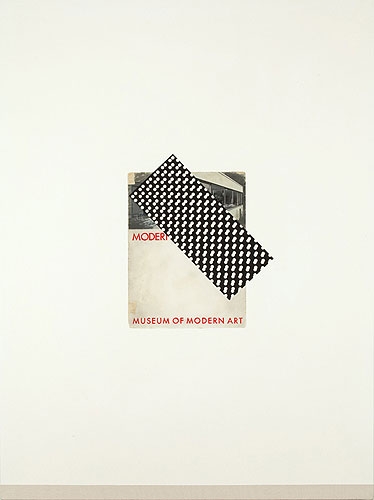

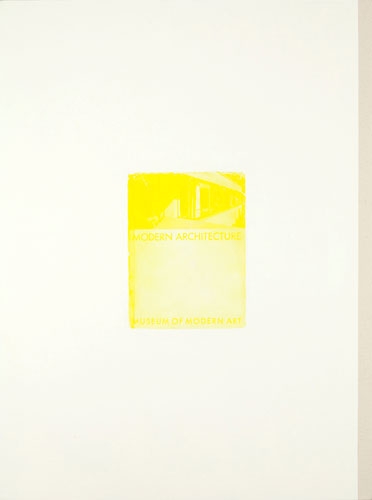

Also in the first room of the gallery, Babak Radboy has installed a wall text which runs from the ceiling all the way to the floor of the gallery. While reading like a legitimate if not over-long and perplexing description of the show, the text is in fact a programmatic collage composed entirely out of sentences from the press releases of every preceding show at Sfeir-Semler. Four headphones hang from the same wall playing looped recordings from the New York Museum of Modern Art's audio-guide for the blind. The recordings have been edited to omit all titles of works, names of artists, historical and contextual information- leaving only surreal and vivid descriptions of figures, forms, materials and measurements.

Storage Room

In an adjacent nook hangs the contents of Sfeir-Semler's storage room, hung indiscriminately in the salon style in a room in which an eight foot tall cube has been built leaving only a two foot wide passageway in which to view the works. The room stands as an object lesson in which the brief and illusory unity of curration is collapsed by the business of running a commercial gallery.

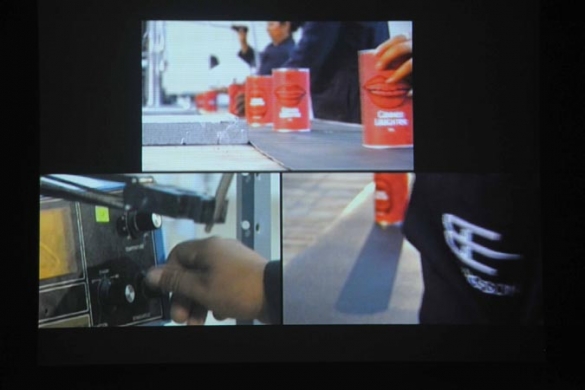

STEP 1: FILL CUPS WITH BEER

- Fill 20 cups 1/3 full with beer.

- Mr. Kosten, can you please tell us where the game got its name from?

- The first distant tremor wakes me up.

It is a bright morning and the sea outside my balcony is splashing in a friendly way against the promenade.

I decide to sleep in.

It is Sunday morning.

- At twenty two past six on a still Sunday morning,

a Mercedes truck with a yellow railed bed and a gray cab,

entered a parking lot two hundred meters South

of the four story Battalion Landing Team (BLT) headquarters at Beirut International Airport.

STEP 2: ARRANGE CUPS

- Arrange the plastic cups in 2 triangles of 10 on opposite ends of the table with the tips pointing to the center.

- Thinking back, I believe that the game got its name based on an analogy between

ping-pong balls flying across the table and landing on the opponent’s side;

and an idea that the U.S should bomb Beirut as a result of the casualties in the area.

The name of the game reflects respect for the Marines and the U.S losses in the region.

- A few seconds later,

another gentle quake,

a very slight, intimate change in the air pressure in the house.

A second bomb.

I lie in bed for another four minutes.

- The truck was a commercial model with no markings.

STEP 3: PICK TEAMS

- Pick teams of two; one for each end of the table.

- How did the game become so popular?

- The phone rings.

It is my landlord who lives on the ground floor.

His voice is breaking with urgency:

‘MR. ROBERT, MR. ROBERT, IT IS ME, GET UP, GET UP, THEY HAVE BOMBED THE MARINES.

MR. TERRY AND FOLEY ARE LEAVING.’

- Its civilian license plate number was 508292.

STEP 4: TOSS BALL INTO CUP

- One person begins the game by trying to toss a ping-pong ball in any one of the other team’s cups.

Tip: The toss is all in the wrist; so hold the ball at above eye level,

lean in,

and lob it up so it drops down into the cup.

- The popularity of the game stemmed from it being a fast way to get drunk.

It only took 15 to 20 minutes for the consumption of over 10 beers.

As one brother once said:

‘ If you played Beirut, you got bombed.’

- They cannot have bombed the Marines.

Where?

In the street, Anderson is running for his car, Foley beside him, camera dangling from his shoulder.

‘Terry, wait for me.’

Anderson would have gone without me.

He drives fast, viciously, down the Corniche.

Foley’s face is fixed on the road and he talk without looking at me.

‘ They got the Marines and they got the French, car bombs. That’s all the radios are saying?’

‘How?’

- In the basement of a building fifty meters to the North,

I lay awake on my cot beneath a tent of green mosquito netting.

STEP 5: IF THE BALL MAKES IT IN…

- A member of the opposing team has to drink the cup of beer it lands in.

If the ball misses, it is the other team’s turn.

- I heard that in addition to organizing Beirut tournaments,

the brothers of Theta Delta Chi created a Beirut table with the map of Beirut on it.

If the game was so popular, why did you advise against playing it in your fraternity after a while?

- Foley is angry.

‘How the hell do I know? It may be a load of crap but I heard the explosions.’

The airport road is deserted,

but there is a cloud of white smoke steaming upwards from the far end where the Marines are based.

- The soft methodical breathing of those sleeping around me,

a beam of early morning sunlight sparkling with dust motes slanting into the room from the doorway,

the smell of dank air.

STEP 6: IF THE BALL LANDS IN AN EMPTY CUP…

- You have to drink one of your own beers.

Tip: Set aside a cup filled with water so the ball can be rinsed off if it lands on the floor.

- The poor judgment and behavior the game encouraged troubled me.

So when I spoke to my successor as President of theta Delta Chi,

I told him that the one thing he could do for the benefit of the house,

would be to cut up the Beirut table with a chainsaw.

- ‘We’ll find Bob Jordan. You try to find him in the press room, I will look for him in the BLT.’

But when Anderson stops the car, he is frowning.

- I’ve always thought that in the moment before a disaster I would feel a precognition,

a sense of dread, of foreboding,

that would prepare me for the cataclysm.

STEP 7: REBUILD TRIANGLES

- Rebuild triangles as you play:

When there are only six cups of beer on a side, make a smaller triangle.

Then do so again when there are only three cups.

- And did he do it?

- ‘ Where is the BLT?’

‘ At the other end of the fence, Terry.’

‘It’s gone.’

‘It’s behind the smoke.’

- Actually the feeling was of laziness and pleasantness.

STEP 8: WINNING

- Keep going until one team wipes out all the cups on the other side.

The winners get to make the losers drink the remaining cups on their side.

- No he didn’t.

But the Beirut table did not survive into the 1990’s.

- ‘ It isn’t.

It fucking disappeared.’

- Sundays were usually relaxing days highlighted by a picnic and a spirited game of volleyball.

FIRST TO CONTAIN A GESTURE

THEN TO FOLLOW A CURVE

& THEN TO SUPPORT A FOLD

EACH TRANSITION ACQUIRING A NEED OF IT'S OWN

FULL CIRCLE

Also making her exhibition debut is gallerist Andree Sfeir as herself with an edited sound recording of a conversation she participated in with the curators.

THE DAILY STAR

February 05, 2010

Sfeir-Semler exhibition falls short of curator’s challenge, but offers some pleasures

by Jim Quilty

NOW LEBANON

December 16, 2009

Make some NOISE

Sfeir’s show challenges the idea of art galleries

by Lucy Fielder

read article at nowlebanon.com

The blurb on the wall as you enter Sfeir-Semler’s NOISE gives a taste of things to come.

It appears to describe the gallery’s latest show, but has no relation to it at all.

“It’s sort of a joke by the curator,” explains Sfeir’s assistant director, Peter Currie. “It’s actually a mish-mash of phrases from blurbs from previous exhibitions.”

Look for clues from the headphones plugged into the wall and you’ll be disappointed the rolling audio guide describes another show, all the way over in New York at the Museum of Modern Art, for the benefit of the blind.

NOISE is no conventional exhibition, but a mischievous challenge to the idea of galleries, such as this one in the Karantina industrial zone north of Beirut, and the way they present art.

NOISE “attempts to close its eyes and tune its ears to the white noise of the white cube,” according to the show’s real description, and to question how much the frame and context the gallery, the visitors and the city affect the art. Curated by Negar Azmi and Babak Radboy for the Bidoun contemporary Middle Eastern Art magazine, the exhibition opened on Friday and will run until February 6.

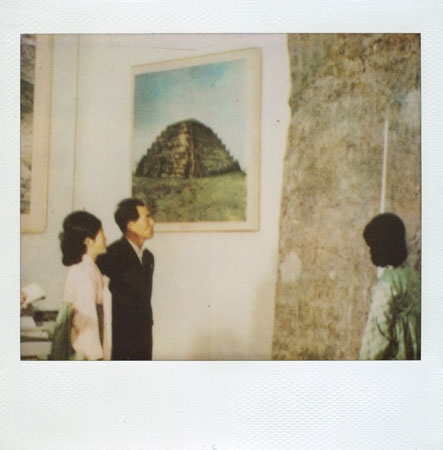

One of the clearer examples of this is the room exhibiting unsold work from a previous show by Syrian painter Marwan. A large white cube takes up the center of the room, leaving just a narrow perimeter, cramping visitors against the works and forcing them to view them at an uncomfortable proximity.

Walead Beshty sent a series of copper blocks to the gallery by Fed-Ex, via other points on the globe. They are displayed as they arrived, smudged with fingerprints, grubby and plastered with stickers: the opposite of taking a pristine work of art and displaying it in a blank white cube with no interaction with the world outside.

“They’re only considered works of art once they arrive at their destination, they have a story, they have a life,” Currie says. “It’s a meditation on minimalist practices.”

Beshty’s series of photographs from film damaged by the X-rays at Beirut airport, meanwhile, explores globalization and what Currie calls the “residue of travel”.

Art and elitism

Several works highlight the exclusivity of the modern gallery, which often seems to aim at an elite (try reaching Sfeir-Semler without a car, for example).

One such is visible from the highway: Vartan Avakian’s sign spells out Sfeir-Semler signposting the usually unmarked gallery for the first time in the Indian Devengari script, for the benefit of Asian migrants in nearby Bourj Hammoud. Inside the door is another sign in Armenian.

New York-based artist Steven Baldi has blocked off part of the space with a glass wall, forcing visitors to retrace their steps back through the show to see the works again, and also drawing parallels with the “glass ceiling” and the invisible barriers created by class and wealth.

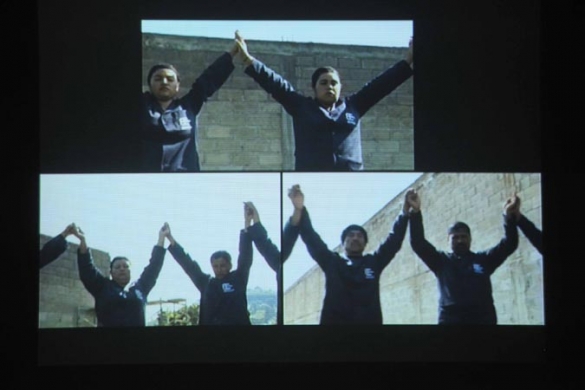

NOISE is often playful; architect Rayyane Tabet’s sculpture represents a drinking game called “Beirut”, which was dreamed up by US military personnel based here.

And Bassam Ramlawi makes his debut with a series of works based on Dutch painter Rene Daniels’ explorations of artistic perspective; it turns out that Ramlawi is the invention of Lebanese artist Mounira Solh.

NOISE is a conceptual exploration, provocative and far from easy. It raises a smile and some interesting questions, and so even for those who like their art a little more conventional, it is well worth a trip.